People often bristle when they hear someone say privilege because of the meaning they attach to the word. Most associate the word “privilege” with wealth and having been given something you didn’t work for. Understandably, they may react something like this: “What do you mean I have privilege? I didn’t go to private school in England. My family comes from poverty. I worked hard for every dollar in my bank account.” Having wealth, getting an inheritance, or attending elite educational institutions absolutely does confer privilege.

But wealth and societal class are not the only ways that people can have privilege.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines privilege in this way:

A special right, advantage, or immunity granted or available only to a particular person or group.

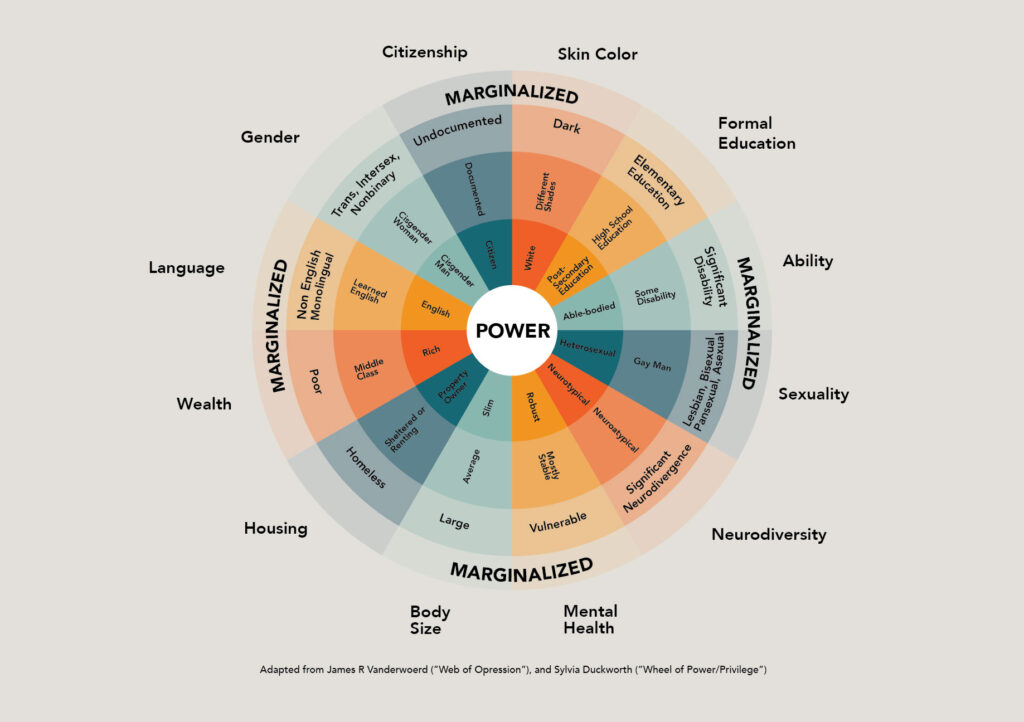

In our DEI work, privilege refers to unearned advantages conferred upon individuals due to attributes like race, gender, socio-economic status, ability, and sexual orientation. These advantages are systemic and often go unnoticed by beneficiaries. Privilege isn’t about merit or effort. It’s about the circumstances of one’s birth or societal context. It’s also relative: a person might be privileged in one context and marginalized in another. For example, someone might have the privilege of wealth in one setting, but experience discrimination based on race in another.

Everyone has some form of privilege, but the scale varies based on numerous factors.

This wheel presents a good illustration of the many forms privilege can take.

Where would you place yourself in each of these categories?

When we look at this broader definition of privilege, we can see that we ALL have some privileges in some circumstances. And some people, through birth or life circumstances have more privileges than others.

Here are some common examples of privilege:

White Privilege: White individuals, particularly in Western countries, usually don’t face racial discrimination in their daily lives, have a higher likelihood of seeing people of their own race represented in media, and are less likely to be racially profiled.

Male Privilege: Men don’t face gender-based violence to the same degree as women, might earn higher wages for the same work, and are often overrepresented in leadership roles.

Heterosexual Privilege: Heterosexual individuals aren’t discriminated based on their sexual orientation, have their relationships legally recognized everywhere, and see their relationships frequently represented in media.

Able-bodied Privilege: Those without disabilities may take for granted their ability to access buildings, transportation, or information without additional assistance or resources.

Privilege isn’t intrinsically good or bad. Having it doesn’t diminish your achievements. Nor does a lack of it diminish your worth.

Human beings are biologically hardwired to classify people based on certain criteria. This happens in a nanosecond without our conscious control. It’s the way our brains work and how our social systems work. We reflexively grant more power to those closer to societal “centers.” When we look at society and our places of work through this lens, it’s easy to see that the people who have more privileges are more visible. They hold more leadership positions. They make the rules for others to follow.

The challenge lies in recognizing these privileges.

Those in privileged positions often mistakenly believe opportunities are uniformly available since they see others like them in power. Discrimination or disadvantages might be invisible to them because they haven’t personally faced them. Empathy is the ability to see the world from someone else’s perspective. The guidance to “check your privilege” is simply a reminder to consider if your actions or words are influenced by your societal standing. Knowing how people stand in relation to other people is a foundational piece of inclusive leadership. It helps you identify who might be excluded or overlooked or have a disadvantage in a situation – giving you a chance to level the playing field.

When we pay attention, we can become aware of privilege and make changes in how we lead.

Let’s look at language privilege as an example.

In a meeting with predominantly English speakers, people who are ESL have a disadvantage. They may be quiet in a meeting because the conversation is moving too fast for them to keep up. They must work harder to understand what is being said and to formulate their thoughts in a different language. This doesn’t make them less intelligent or make their input less valuable. (On the contrary, gaining access to their unique perspective is part of what makes diversity so valuable.) However, in this context, the English speakers are privileged. They have an advantage that the ESL person doesn’t have. An inclusive leader would recognize this situation, realize that this person has something to contribute, and make changes to the meeting structure or environment to help support that person to thrive.

This is also a good example of how privilege can change with the situation and context. If the meeting was conducted in the non-native speaker’s primary language, the privilege dynamics would reverse. Grasping the essence of privilege is essential for understanding societal power dynamics and building skills as an inclusive leader.

Recognizing, reflecting upon, and responsibly acting on our privilege can pave the way for more inclusive, empathetic, and equitable interactions in both personal and professional settings.